Editor’s note: Flood: One year later is a multipart series exploring how the devastating November 2021 flooding changed the lives of Whatcom County and Skagit County residents, as well as bodies of government, over the past year. From farmers to mayors, the historical flooding led to economic challenges, developing plans for the future and preparative measures. Today’s final in the series explores how the flooding affected farmers in Whatcom and Skagit counties, in both finances and production.

During the flooding in Whatcom and Skagit counties last November, farmers watched their crops drown, their equipment wash away and their tractors take a swim. When Skuter Fontaine of Everson went to pull out the dipstick in his tractor’s engine after the water receded, water streamed out for 30 seconds.

The floods, which caused $150 million in damage in Whatcom County, including $27 million in agricultural industry damage, made Fontaine rethink what crops to grow, when to harvest and what to invest in.

Fontaine has owned Terra Verde Farm since 2016, but last year was the first time he had seen the Nooksack flowing north, rushing across his farm outside of Everson.

“We were fighting the water, trying to keep it out of our house,” Fontaine said. “At a certain point, around 1:30, 2 in the morning … there was just such a flush of water that it overtook any efforts to fight it.”

Fontaine decided to go to sleep and assess the damage in the morning.

Now, Fontaine estimates his farm experienced tens of thousands of dollars in damage, from crop loss to equipment being washed away. Before last year, he understood some of the flood risk and challenges that came with farming this area, but it took on a different meaning last year.

“It was just a mess. And we were lucky, regardless of how shitty it was for us,” Fontaine said. “We’re definitely way luckier than so many other people, and that’s not really a great way to look at it or be optimistic, but I’m just trying to find ways to put situations into perspective.”

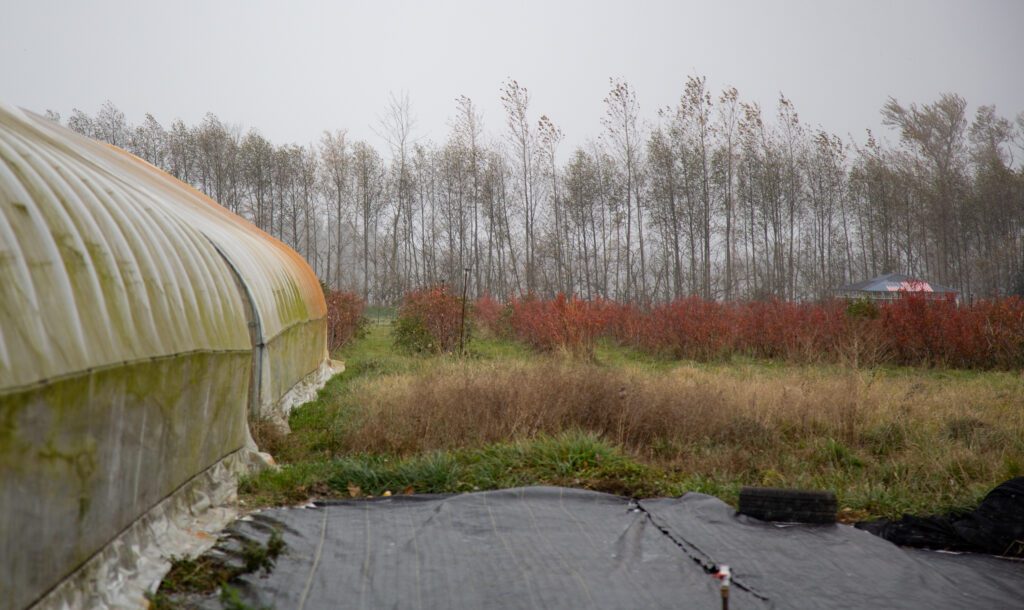

Since then, Terra Verde Farm has shifted its focus more to perennial crops that don’t grow over the winter. Instead of growing overwinter leeks, Brussels sprouts and cabbage, Fontaine has invested more in blueberries, peonies, asparagus and grapes, crops that grow throughout the spring and summer and can be harvested before flood season, he said. “We’ll see if it works.”

Fontaine hopes to bolster his greenhouses and his home to be more flood resilient in the hopes of not having to leave and abandon his investments. “When we bought this place, it took every last dime we had. We really put everything that we could muster up towards it.”

Agricultural industries have a significant influence on the economies of Whatcom and Skagit counties. In 2017, crop harvests brought in $154 million in Whatcom County, with $114 million of that being from fruits, trees and berry crops. In Skagit County, crops were valued at $182 million, with vegetables, melons and potatoes having the largest economic influence, according to research from Washington State University.

Flooding takes its toll on farms after the waters recede, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture recognizes crop and equipment loss and soil erosion as some of the major long-term challenges flooding presents. In addition to those losses, flood waters contaminate any crops that don’t get washed away, making them difficult or impossible to sell depending on the river and the type of contaminants.

At Farias Farm in Skagit County, Francisco Farias watched 5 feet of water submerge his 6-acre farm on the edge of the Skagit River. The water flooded his greenhouses, damaged a tractor, mower and generator, and washed away seeds he had placed carefully on a table 2 feet above the ground. That height did nothing to keep them dry, he said.

“I was thinking like maybe 1, 2 feet,” Farias said. But when he saw the flooding, he thought, “Oh wow, nothing is going to be safe.”

Farias estimated his damages were close to $10,000. In the future, his flood plan is to load up everything transportable and bring it to his other farm nearby, which doesn’t have a flood risk. Farias knows he’s lucky to be able to move to higher ground if severe flooding returns.

The flooding last fall impacted Farias Farm, but they were able to come back from it, Farias said. This summer’s harvest was fine, but he’s hoping the river doesn’t flood this winter.

“For us it was bad, but not too bad,” Farias said. “I don’t want a surprise.”

If flooding happens more regularly, Farias doesn’t know if he will keep farming this land or stop growing overwinter crops. Farias Farm sells at farmers markets in the Seattle area year-round, but if floods start impacting what he can harvest in the winter season, he may not grow as much at Farias Farm or will change the types of crops.

While he hopes there won’t be flooding, he’s doing his best to be ready. He will pack up everything into trucks and move if he has the time.

“We have to be ready every time because we never know,” Farias said. “The only support I have for me, for the farm, for my family, is the farm.”

Julia Lerner contributed to the reporting of this story.

Series credits

Reporter Olivia Hobson is a fall quarter intern at Cascadia Daily News. She studies environmental journalism and geographical informational sciences at Western Washington University, where she will graduate in December. Hobson previously wrote and edited for the quarterly environmental magazine, The Planet.

Photographer Hailey Hoffman is a visual journalist and education reporter at Cascadia Daily News. She joined the team after two years as a staff photographer for The Astorian on the Oregon Coast and is a graduate of Western Washington University.

Editor Audra Anderson is the assignment editor at Cascadia Daily News. She previously worked for Wahpeton Daily News in Wahpeton, North Dakota, as a reporter, then assistant managing editor. There, she honed her reporting, editing and design skills in a small, but capable, newsroom.