I survived my most harrowing roommate experience in August 2017, subletting a room in a Happy Valley apartment. Claire, the girl who lived in the bedroom across from me, who was kind and courteous and rarely home thanks to our opposite work schedules, was innocent.

The roommates in question had eight legs.

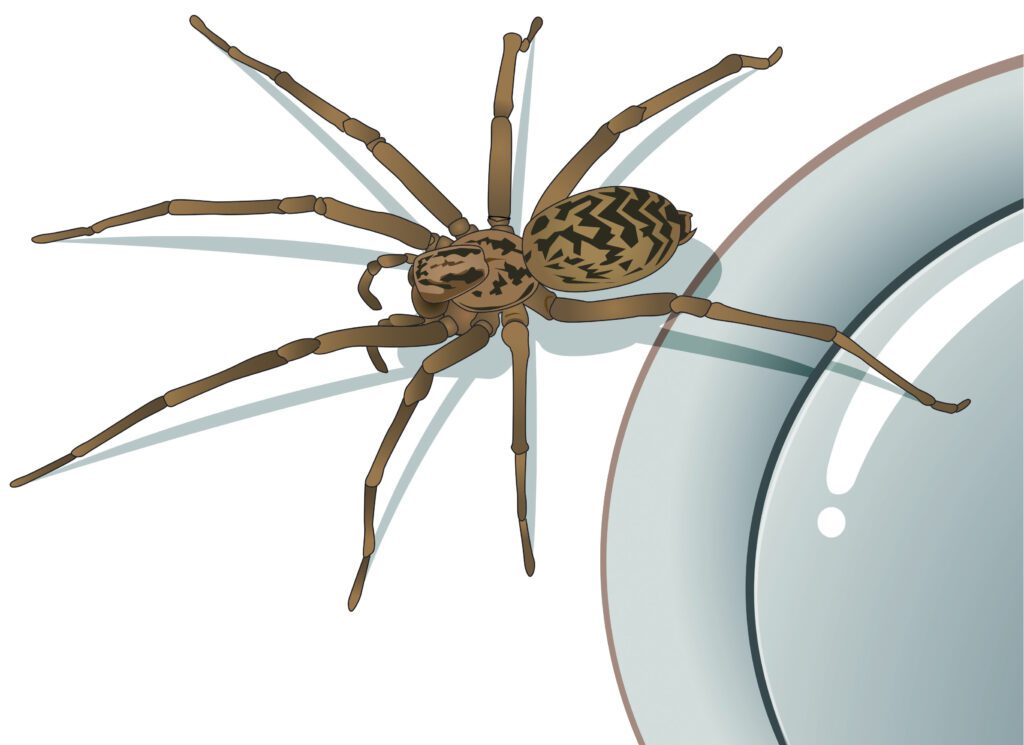

As someone who has been scared of spiders since a transformative slipper-under-the-bed incident at age 5, I remember reaching peak terror in my Bellingham apartment toward the end of that August. When I got home from work one day, a giant house spider, the biggest I’d seen yet, sat on my bedroom floor a foot from my open door. My arrival startled the thing, and it scuttled under the wooden pallets that elevated my mattress.

Help, in the form of Claire, arrived home a few hours later. I tearfully told her of the “monster under my bed.”

Humans are adept at coming up with “Old Wives’ tales” and myths and superstitions to make ourselves feel better and assert more control over nature (think: ants won’t cross a line drawn in chalk). Claire had one, too: marijuana smoke forces out spiders.

That night, she took a bong rip, holding it in her lungs as she dropped to all fours on the floor and blew an outpour of skunky smoke under my bed. I watched from atop a chair. The spider did not emerge.

I resolved to sleep on the couch, unable to be in my bed knowing it was beneath me. When I lifted up a cushion to swap it with my bedroom pillow, there cowered another eight-legged creature.

I recall feeling cinematic, as I reeled back, trembling, tears rolling down my cheeks, taking in all the spiders in my vicinity: the ceiling spiders, the corner-of-the-wall spiders, the shoe-pile-by-the-door spiders.

I spent the last two weeks of my sublease sleeping at a friend’s.

Then, I spent the next six years peddling several fallacies to Western Washington newcomers: “Spider season” in August and September is supposedly when the arachnids journey indoors seeking warmth, and it was the reason for the eight-legged infestation of my 2017 apartment.

House spiders are roommates, not guests

In reality, there is no Bama Rush of spiders entering homes come late summer and early fall; 95% of the ones you see in your living spaces have never even been outside, according to Rod Crawford, curatorial associate (arachnida) at the University of Washington Burke Museum.

“If an outdoor spider does come in, it’s strictly random wandering,” said Crawford, Washington’s leading spider expert.

Plus, spiders are not attracted to warmth, he said, and the months of May and October are actually when the greatest number of species in Western Washington reach maturity.

Why, then, does anecdotal evidence (and plenty of NextDoor app complaints) seem to suggest an invasion is underway in August and September every year?

The giant house spider, “which probably scares more people in Western Washington than any other,” matures at this time, Crawford said. After the final molt that makes them mature, the giant house spider develops functional sex organs and the males go in search of a mate.

“That means a lot of moving around,” Crawford said. “And if you’re a giant house spider — which live almost exclusively in buildings, and which are up to 4 inches in diameter — moving around means you startle a lot of arachnophobes.”

In August and September, the giant house spiders are larger and become more conspicuous, leading many to believe they weren’t indoors in the first place. But they were. (A pause, for those of you undergoing the five stages of grief right now, struggling to advance past “denial.”)

The giant house spider, native to southern England, has been adapting to indoor life since the days of the Roman Empire, Crawford said. Their egg sacs may get carried in on building materials, or later, on moving boxes and furniture pieces.

Most of the time, the creatures, along with a few dozen other spider species commonly found indoors, are living in crawl spaces and basements, floorboards, wallboards, cracks and crevices, behind furniture and appliances, and in seldomly vacuumed areas.

‘Wave as they go by’

Crawford’s advice for seeing a spider crawling on your wall or scuttling across your carpet: “Just wave as they go by.”

We can all strive to reach that level of nirvana. In the meantime, the benevolent among us may choose the cup/paper or rolled-up newspaper method of catch-and-release over the lethal shoe or vacuum or spray.

Bad news, big hearts: You might have sentenced the spider to death anyway.

“You can’t put something back outside which has never been outside and is not really well adapted to environments like lawns and forests,” Crawford said.

Instead, consider moving a house spider to a garage, shed or crawl space; the creature would at least have a fighting chance of survival in a familiar habitat, he said.

Leave your backyards to the spiders that belong there, like the cross orbweaver. The web-weaving outdoor species might startle you if you’re picking blackberries in your garden, as it, too, matures this time of year.

Crawford also dispelled common prevention tactics people employ this time of year. Ultrasonic bug repellers are a scam, spiders are not known to detect airborne scents (like mint), the color light blue does not repel the creatures.

And, “do not call Mr. Pest Control man to do a perimeter treatment around the outside of your building,” Crawford said. “That accomplishes nothing except enriching them and adding more pesticide pollution to the environment.”

To see fewer spiders in your living spaces, seal cracks under baseboards, in floorboards, in walls, and near pipes, conduits, and appliances, and weatherstrip beneath basement or garage doors.

Education ousts fright

For those of us who are well-intentioned but petrified of the tiny creatures, is there hope of reaching a comfortable coexistence? Crawford thinks so.

Education is the antidote to fear.

The 71-year-old scientist thinks he had a “mild spider fear” before he began researching them in high school. Now, Crawford has expanded Washington’s documented species list from a bit less than 300 to 970 and counting. In that time, he’s led dozens of classroom programs and considers convincing people of a spider’s merits part of his work.

“Spider fears are learned,” Crawford said. “The younger the group of humans you deal with, the fewer are afraid. By about the sixth grade, practically all of them are afraid. But if it’s first graders, a good half the kids in the classroom are perfectly happy to hold a live giant house spider in their bare hands.”

For true arachnophobes — as in someone whose fear is so crippling they can barely function if they think there’s a spider around — Crawford said to seek therapy, literally. (Phobias are “readily treated by today’s psychotherapists.”)

On the spectrum of fright, where Crawford is on the left and arachnophobe is on the right, I think I fall somewhere far right of center. But in my quest to educate myself, I have made progress. I am able to look, mostly unaffected, at the pictures of spiders I’ve pulled up on my screen throughout the course of writing this column.

Maybe one day, I will reach a point of waving to my tiny roommates — even if they don’t pay rent.

Web of lies — Debunking persistent spider myths

Rumors and myths harm spiders far more than any harm they cause us. In fact, no species in the Western Washington mainland is a danger to humans, Crawford said.

Of the tens of thousands of live spiders he’s held in his bare hands, Crawford said he’s only been bitten three times.

While arachnophobes may fantasize about a world absent of spiders, that would be a terrible world, Crawford said.

Somewhere between 40–50% of all insect biomass ends up passing through spiders, Crawford said, citing isotopic tracer studies. That means without spiders, land life on Earth would consist primarily of insect species that would go through “boom and bust” cycles like locusts. Only their populations wouldn’t fall until the available food was gone — including our food, Crawford said.

Crawford dedicates a portion of his career to debunking myths about the creatures. A webpage on the Burke Museum website, written by Crawford, lists then busts common fallacies. Here are a few of the ones I’ve heard:

You swallow spiders in your sleep.

False. Spiders are rarely near you when you’re sleeping and are not attracted to the moisture in your mouth. “For a sleeping person to swallow even one live spider would involve so many highly unlikely circumstances that for practical purposes we can rule out the possibility,” Crawford writes.

Most unidentified bites are spider bites.

False. Spiders must be standing on something to bite it, since their fangs are located underneath the spider. The likelihood of a spider bite occurring at night while you’re sleeping is extremely unlikely — in reality, if a spider somehow ended up in your bed, they’d probably be crushed to death from the weight of your body before they ever bit you (or even the sheets). Mystery bites cannot be attributed to spiders.

Spiders come up through drains.

False. Any spiders that end up in tubs or sinks were house spiders trying to reach water. They then become trapped in the slick, porcelain environment, and require a human to help them out.

All spiders make webs.

Only about half of known spider species catch their prey in webs. The other half hunt their prey, or wait for prey to come to them. All spiders produce silk, and hunting varieties may use their silk for egg sacs or silk “houses,” according to the site.

Webs are typically geometric orbs.

Spiders make four major types of web, depending on the species: sheet, funnel, orb or cobweb. Sheet webs, the most common type, and cobwebs are not sticky.

Find more information on the Burke Museum website, and check out Rod Crawford’s online Spider Collector’s Journal.