Across the West Coast, communities are scrambling to find innovative ways to support wild salmon and trout populations that have collapsed significantly over the last century.

In California and Oregon, bans on chinook salmon fishing will prevent all commercial and most recreational fishing along the coast from northern Oregon to the California-Mexico border through the fall.

In waters around Washington, populations of already endangered chinook salmon and steelhead trout continue to fall, with current populations clocking in at just 3-4% of what they were in 1900 in Puget Sound. Scientists predict that decline will continue, with projected salmon survival rates expected to diminish by 90% over the next four decades.

In Washington, state leaders and tribal representatives are working tirelessly to solve the problem, conducting habitat mitigation and pouring millions of dollars into their work. Now, state representatives are mulling plans for future hatchery management to allow continued fishing. But leaders are asking: Is it enough?

Under Washington’s current hatchery policy, hatcheries address three designated concerns: conservation, mitigation and fishery supplementation. Under conservation programs, the hatcheries serve to bolster “depressed target wild salmon or steelhead populations that are in need of rebuilding or recovery,” according to the state’s current hatchery management plan, referred to as 3624.

Mitigation programs help produce salmon and steelhead to “offset adverse impacts” from projects associated with habitat degradation, and supplementation programs help local fisheries meet watershed-specific goals.

Around Washington, a majority of the hatcheries are managed by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, or co-managed with local tribes like the Lummi Nation.

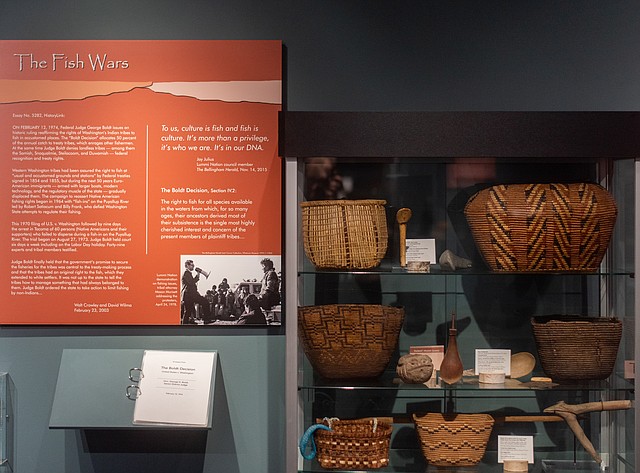

And, the tribes say, hatcheries are vital to supporting Indigenous ways of life and fortifying treaty rights — in place since the 1800s and protected by the Boldt Decision — after decades of environmental degradation.

Part of Whatcom Museum’s “People of the Sea and Cedar” exhibit includes information about the Boldt decision, which upheld the rights of several Western Washington tribes to fish with nets off reservations. (Finn Wendt/Cascadia Daily News)

Part of Whatcom Museum’s “People of the Sea and Cedar” exhibit includes information about the Boldt decision, which upheld the rights of several Western Washington tribes to fish with nets off reservations. (Finn Wendt/Cascadia Daily News)

“Robust natural-origin salmonid populations do not exist in close proximity to robust human populations,” Tom Chance, a fisheries biologist and hatchery project manager for the Lummi Nation, said in an email. Hatcheries “are necessary to meet tribal Treaty obligations and sustain tribal ways of life until the political will and financial backing to actually reverse the trend of habitat degradation are realized.”

Chance doubts that political will or financial backing exists to restore the decades of lost habitat.

“We are still losing habitat faster than it can be protected and restored,” he said. “If we didn’t have local salmon hatcheries there would be no salmon fisheries available,” with few exceptions.

In 2022, tribes released more than 39 million salmon from hatcheries, rearing ponds, marine net pens and incubation facilities across the state. Only a small fraction survive in the ocean to return to spawn in local streams.

Efficacy of hatcheries in question

Meanwhile, pressure from conservationists who believe hatcheries are detrimental to wild stocks continues to mount. Though hatcheries have been in use in Washington for more than 100 years, new science shows they may not be working as intended.

“There’s a tremendous amount of literature out there that describes what’s been going on, how long it’s been going, how misguided it is, how well-intentioned it was at the start,” said Hugh Lewis, a board member of the Wild Fish Conservancy. “But circumstances and the overriding laws of genetics ultimately proved that the system that they put in place … was flawed from the beginning.”

Though hatchery fish help prop up salmon populations for fishing and treaty requirements, the fish can pose challenges to wild salmon, including habitat competition and illness, he and others say.

“Here we are almost 100 years later, living in the wreckage of all this,” Lewis said.

The Wild Fish Conservancy, a nonprofit conservation organization working to support wild fish populations across the West Coast, has advocated removing hatcheries from state management practices for years. The group has sued the Department of Fish and Wildlife, as well as the Fish and Wildlife Commission, several times in the last decade, attempting to stop the state from using hatchery programs with non-native fish. Lawsuits filed by the group in 2014, 2019 and 2021 have not halted the use of hatcheries to propagate local waters.

Even the existing management policy, 3624 — which took effect in the state in April 2021 — identifies threats to wild fish from hatchery-produced salmon and trout. The policy recognized genetic and ecological risks posed by hatcheries to wild salmon and steelhead populations, including disease transmission and competition, as well as increased predation and “hatchery facility effects.”

Washington’s 2022 “State of Salmon in Watersheds” report, issued by Gov. Jay Inslee’s Salmon Recovery Office, said “hatchery and harvest management reform” is necessary to achieve the state’s lofty salmon recovery goals. The report also identified hatcheries as a “challenge” facing salmon and trout recovery.

No salmon species in Washington have been removed from the federal Endangered Species Act list, the report said, and indicated most salmon populations are either “in crisis” or not keeping pace with recovery goals. The ESA, passed in 1973, marks the distinction between wild and hatchery-grown salmon.

Chance said hatchery science is heavily debated, but the fact remains that hatchery fish are serving local populations.

“Hatchery science is very complex and poorly understood,” he said. “The reality is that there is a conspicuous lack of legitimate, empirical evidence for many of the claims made about the various risks hatchery-origin fish pose to their natural-origin components.”

Lewis pointed to significant environmental and health concerns with hatchery fish, and said they cannot compare with wild salmon. While hatcheries have provided fish in abundance for people to catch, those same fish are not as adept at surviving in the wild, are generally smaller and have lower reproductive success compared to wild fish.

“Not all chinook are created equal,” Lewis said. “The chinook that are produced in our salmon hatcheries … they’re half the size of a 4- or 5-year fish, which is what the orca populations prefer.”

Southern Residents rely on salmon recovery

The politics of salmon recovery are intertwined with that of the Southern Resident orcas, critically endangered whales that reside in interior and coastal Washington waters. The three pods, composed of just 73 orcas, are some of the last salmon-eating orcas in the world.

Chance disagreed with Lewis’ assertion that hatchery fish are inferior to wild fish for the orcas, saying the Southern Residents rely on hatchery fish, just like humans.

“Because the majority of chinook present in much of the migratory range of these whales originated from hatcheries, we can confidently assume that hatchery chinook greatly benefit” the Southern Residents, Chance said in an email.

Part of the problem, Lewis said, is genetic diversity in the fish. Salmon spawned in the Nooksack River in Whatcom County wouldn’t survive as well in other rivers, and historically, hatcheries didn’t respect that.

“We wiped out the fish that had been best for that habitat under principles of local adaptation,” Lewis said. Early hatchery managers “figured these fish are more or less fungible and no harm would be visited upon anybody or anything, and it would be totally beneficial to have this hatchery system.”

In hatcheries, the fish tend to be genetically weaker, less able to survive in the wild and contributing to low returns of both raised and wild fish.

2014 and 2018 showed some of the worst survival rates on record for salmon populations in the Columbia River Basin, according to an investigation from ProPublica and Oregon Public Broadcasting. That decrease was in part due to hatchery fish.

Lisa Wilson, vice chair of Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission and member of the Lummi Indian Business Council, maintains the hatchery fish are part of the tribe’s treaty rights.

“It is the state’s obligation to make sure that we will have not only salmon to continue our way of life, but also the habitat to sustain them,” she wrote in an email. “Our Treaty right which is the supreme law of the land is not going to be dictated by a few opinions.”

Even so, the high financial burden of operating the facilities and the increasingly low population returns mean Washington is considering other options.

The federal and state governments have continued to support hatcheries across the country, pouring more than $2.2 billion into them over the past 20 years. Along the Columbia River, the government spent between $250 and $650 per salmon that returned to the river last year, according to the ProPublica and OPB investigation.

Members of the state Fish and Wildlife Commission want to prioritize conservation and environmental concerns in fish hatchery management. Currently, commissioners are discussing new management plans, including a new co-manager policy, to coexist with 3624.

Commissioners will meet again this summer to hash out details of the co-manager policy in conjunction with 3624, and weigh hatchery impacts on wild salmon alongside the Southern Resident orcas.