Endangered salmon populations across Washington are still falling, despite ongoing recovery efforts and millions of dollars spent on restoration projects. In Whatcom County, though, bright spots are emerging.

In the face of statewide struggle, local tribal efforts, including manmade logjam projects, land acquisition and dam removal along the Nooksack River, have been lauded as major advancements in recent years.

Around the state, salmon populations have fallen, with 14 different population groups of steelhead trout and chinook, coho, chum and sockeye salmon listed as threatened or endangered in Washington under the Endangered Species Act, according to a new report from the Governor’s Salmon Recovery Office. The 2022 State of Salmon in Watersheds indicates more trouble for the fish, a significant problem for tribal entities and habitats that rely on healthy, sustainable salmon populations.

Still, the report, released in late February, highlights a few “bright spots” in Washington state, including ongoing habitat restoration efforts like the dam removals in the Elwha River and the Middle Fork of the Nooksack River.

With fish populations falling, local tribes worry about their treaty rights.

“Treaty rights are being diminished,” explained Lisa Wilson, vice chair of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission and member of the Lummi Nation. “We’re doing all the work here, bringing the fish back, trying to fix the habitat, and if it wasn’t for the tribes, there would be no salmon.”

In Washington, treaty rights guarantee tribes, including the Lummi Nation and the Nooksack Indian Tribe in Whatcom County, access to 50% of fish harvests in the state, and require the state and federal governments to protect salmon habitat, established in the 1974 Boldt Decision.

Ongoing efforts between local, state and federal agencies, alongside tribes, have not fixed the problem of historic habitat degradation, Wilson said.

“They’ve been trying this process for 20-some-odd years now, and it’s not getting us to recovery,” she said. “We need to think of doing something differently.”

In 2015, Wilson said, the tribe caught “literally just seven chinook” salmon on the South Fork of the Nooksack River. In the years that followed, the tribe worked heavily with the Nooksack Indian Tribe, as well as local and state entities, to bring that number up. In 2020, Wilson said, the tribe saw more than 3,000 salmon running in the South Fork.

Restoration projects along the Nooksack River have been heralded as success stories for salmon populations, as well as their habitat and spawning grounds. Efforts like man-made logjam installations, which the Whatcom tribes initiated in recent years, have been monumental in supporting fish health.

Logjams create pockets of cool, slow-moving water along the river, reduce erosion and create safe areas for spawning.

“These are big, complex projects, but it took a long time to degrade the habitat, and now it will take time to restore it,” Treva Coe, the assistant natural resources director for the Nooksack Indian Tribe, said during a tour of constructed logjams last summer. “The tribe has been a leader of salmon recovery efforts for decades.”

The tribes have constructed hundreds of logjams across the Nooksack River and invested millions into salmon recovery.

In addition to logjams, the tribes have explored land acquisition and pushed for a proposed ban on tubing on the Nooksack last summer, though the ban was not approved by the Whatcom County Council.

Even with successes and local population growth, salmon populations are still far from healthy.

“We brought seven fish up to 3,000, but 2,500 died before they could reach the spawning grounds,” Wilson explained.

The 2020 heat wave that killed several people across Washington also had devastating impacts on salmon, which couldn’t survive the low flows and high temperatures in the rivers.

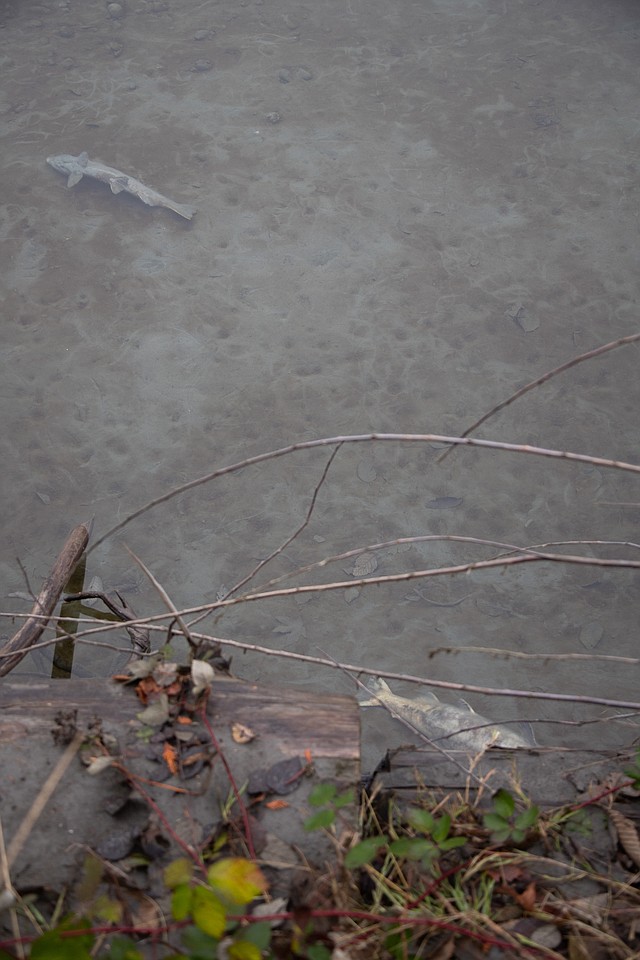

Two dead salmon lay in the river bank after spawning in the Nooksack River in December. (Hailey Hoffman/Cascadia Daily News)

Two dead salmon lay in the river bank after spawning in the Nooksack River in December. (Hailey Hoffman/Cascadia Daily News)

“There have been scientists that have said if we don’t do something different right now, then our salmon could go extinct by 2050, and to us, that’s not an option,” Wilson said. “We will never give up on our salmon, because our ancestors fought so hard to make sure that was the one thing we did secure for ourselves. Salmon is as important as the air that we breathe.”

The local tribes refer to themselves as Salmon People, and rely on the fish for ceremonies, funerals and cultural events.

“Salmon is ceremony to us, and all we’re trying to do is preserve our way of life,” Wilson said.

This year, fish runs are expected to be up in the Puget Sound watershed and along the Washington coast, but the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife said it will keep an eye on recovery efforts.

“We continue to expand our recovery efforts in Washington, but we still have a lot of work to do, and that means some fishing may be impacted again in 2023,” WDFW Director Kelly Susewind said in a March 3 press release.