Schoolchildren across the country have heard the story of Sacajawea, and can readily recall her association with the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804–1806. She is commonly referred to as the expedition’s interpreter.

One has the impression of a beautiful, competent, wise young woman who matter-of-factly guided a team of white men across the Rocky Mountains all the way to the Pacific. The golden dollar coin introduced in 2000 in her honor further solidifies the mythology; it bears the image of a calm, smiling mother with a baby sleeping snugly on her back, glowing with good health.

Not much is known about Sacajawea. She was born around 1788 into the Lemhi Shoshone tribe near what is now Salmon, Idaho. In 1800, when she was approximately 12 years old, she was kidnapped by a Hidatsa raiding party and a year later sold to Toussaint Charbonneau, a French fur trapper, as his second wife. By the time Meriwether Lewis and William Clark agreed to hire Charbonneau and his child bride to accompany them, Sacajawea was pregnant with her first baby, who she gave birth to en route and subsequently carried thousands of miles.

Lest this sound romantic or mild, let’s restate: She was stolen from her family as a girl, raped repeatedly, sold into slavery, forced into marriage with an older man who had multiple wives and compelled to deliver and care for her first child while suffering extreme physical hardship and hunger.

Sacajawea (or Sacagawea, depending on what you were taught and whether you believe her name comes from the Shoshone word for “Boat Launcher” or the Hidatsa word for “Bird Woman”) was only mentioned in Lewis and Clark’s journals a handful of times. Despite their relative silence, she made a major impression on the two, as they named the Sacagawea River after her in 1805. Clark later took her son Jean-Baptiste and her daughter Lizette to raise as his own. Was this a mercy for Sacajawea, or something else?

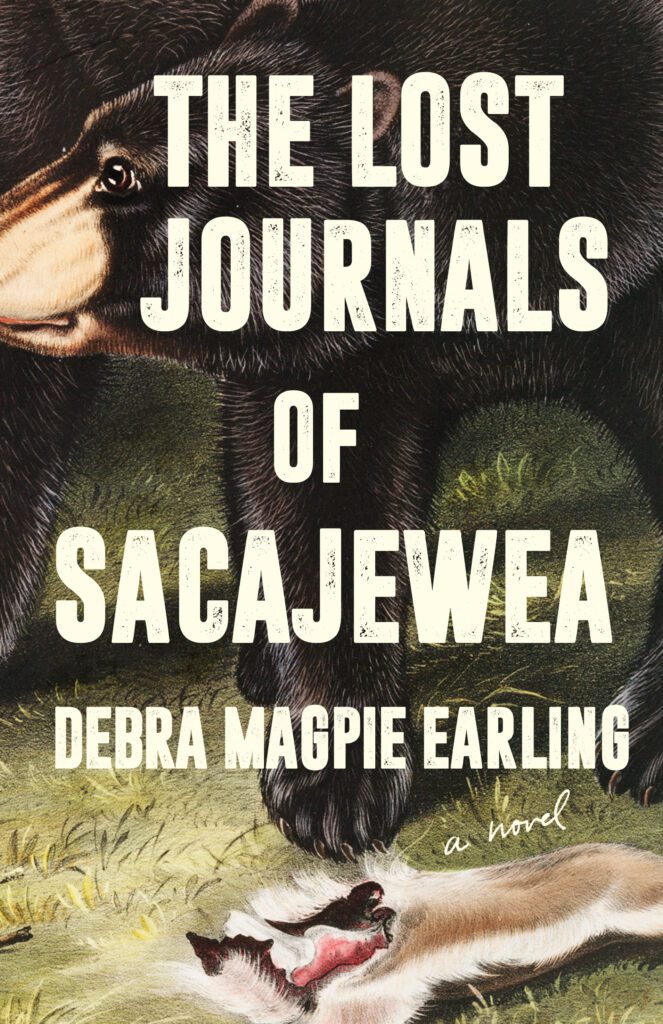

Author Debra Magpie Earling, who is Bitterroot Salish and a retired professor from the University of Montana, takes the bare bones of Sacajawea’s story and invents a rich interior monologue for her, something wholly unique and stylistically challenging. Some will find the broken English, sentence fragments and unfamiliar Shoshone words to be off-putting, or perhaps pretentious. Readers who are willing to puzzle through strange capitalizations and enigmatic descriptions will find keen insights and transcendent beauty.

In “The Lost Journals of Sacajawea,” published in May 2023, Earling’s Sacajawea is observant and pragmatic, a survivor. She is taught by her Bia to work hard and not complain. Through her journals, we get her perspective when white men condescended to teach her English, thinking her ignorant and unsophisticated. Her contempt for Charbonneau is thick and bitter. Her life, so marred by fear and violence, has moments of serenity and triumph. Earling gives non-Native readers a fascinating glimpse of Indigenous ways of knowing and presents a portrait of Sacajawea that is so much more powerful than the whitewashed lore we were fed as children.

“The Lost Journals of Sacajawea” is an excellent companion piece to this year’s Whatcom READS selection, “Red Paint” by Sasha taqʷšəblu LaPointe. Read these books and join in the discussion. A full listing of Whatcom READS events can be found at whatcomreads.org.

Christine Perkins is executive director of the Whatcom County Library System, wcls.org.