LUMMI RESERVATION — With help from the federal government, Northwest Indian College (NWIC) is preparing the next generation of a certain farmer — the type found at Lummi Nation and other coastal tribes. They don’t deal in agriculture, strictly speaking. They harvest crabs, shellfish, salmon and other marine life in a practice better known as aquaculture.

The traditional practices of Lummi Nation fall under the purview of U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which has awarded millions of dollars in grants over the years to the tribal college, to support scientific research and learning. Deputy Agriculture Secretary Xochitl Torres Small, the department’s second-highest-ranking official, visited the college Friday, Feb. 9, to see how the Biden administration’s money was being spent.

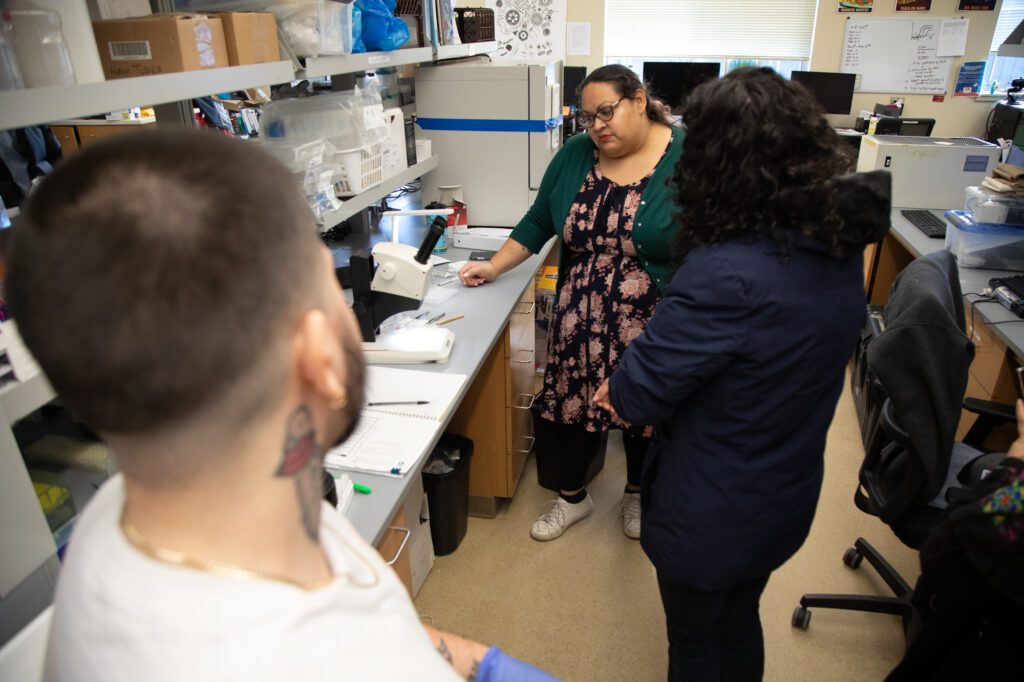

“One of the things that we have an opportunity to do here is make sure that we’re reaching a generation that’s prepared to take on the challenges of the future and the challenges of today,” Torres Small said, after meeting with students and touring the campus. “Visiting Northwest Indian College, I got to meet students who were incredibly resilient, hardworking and had diverse perspectives and experience that grounded the research that they do.”

Torres Small met students who were members of Lummi Nation and Yakama Nation in Washington state, as well as tribal members from Alaska, Arizona and Oklahoma. Students and staff told Torres Small — the first Latina deputy secretary of agriculture in U.S. history — about how they felt out of place in America’s traditional public education system, and how they found a home at NWIC.

The young tribal members are learning cutting-edge technology and processes in aquaculture. In one lab visited by Torres Small, students learn how to deploy a microscope-camera on a buoy, to find toxic algae in Bellingham Bay. The sophisticated floating computer is one of only 42 used in the U.S., said Misty Peacock, director of the Salish Sea Research Center at NWIC.

The USDA awarded the college $2.8 million in October to launch a summer internship program, which will pay a stipend to as many as 20 Indigenous students, who will learn aquaculture locally and at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Peacock said. The grant also pays for student travel and lodging, and will provide scholarships to interns who continue their collegiate education into graduate school.

The award is one of the largest grants NWIC has ever received, Peacock said.

“Ninety-eight percent of the money is for students,” she said. “It’s not for faculty or staff salaries.”

The deputy secretary on Friday also learned about an ongoing USDA-funded study of the longfin smelt native to the Nooksack River. The smelt, known to tribal members as “hooligans,” are a traditional Lummi food.

Little is known about the species, including what it eats or where it ranges across the Salish Sea. Scientists at NWIC hope to learn more about the fish, in order to restore its dwindling population.

At the end of her visit, Torres Small said she came away inspired by the people she met at the college, but she also understood that her department needs to do more to support Indigenous people. Just a generation ago, tribes weren’t even acknowledged in what is perhaps USDA’s most important work product, the federal farm bill.

“I am incredibly inspired and hopeful about the future of agriculture … for Lummi Nation, for Washington and for our country,” Torres Small said. “USDA still has work to do, to be the best partner we can be … I’m grateful to be part of doing that work, and it’s something that will take collaborations like these, to learn how to make that work.”

Ralph Schwartz is CDN’s local government reporter; reach him at ralphschwartz@cascadiadaily.com; 360-922-3090 ext. 107.