LYNDEN — Making a luscious, subtly sweet, silky Icelandic yogurt — also known as skyr — in the Northwest corner begins with the sun. Then, the soil beneath the grass where cows graze.

That’s what Steensma Creamery owner Kate Steensma, 34, likes to say when introducing her product around the region via farmers markets, store shelves, farm tours and word of mouth. The Steensma family farm will be on display Saturday, June 10, for Whatcom This Whey, a behind-the-scenes exploration of some of Whatcom County’s dairy farms, creameries and cheesemakers.

“It’s corny, but I like to say I’m involved in the process from soil to spoon,” Kate said. “We’re farming the grass — the cows are a tool to take the grass, which has no nutritional value to humans, and turn it into protein.”

Sustainability — from grazing rotations of their grass to their glass, reusable yogurt jars — is integral to Steensma Creamery’s brand.

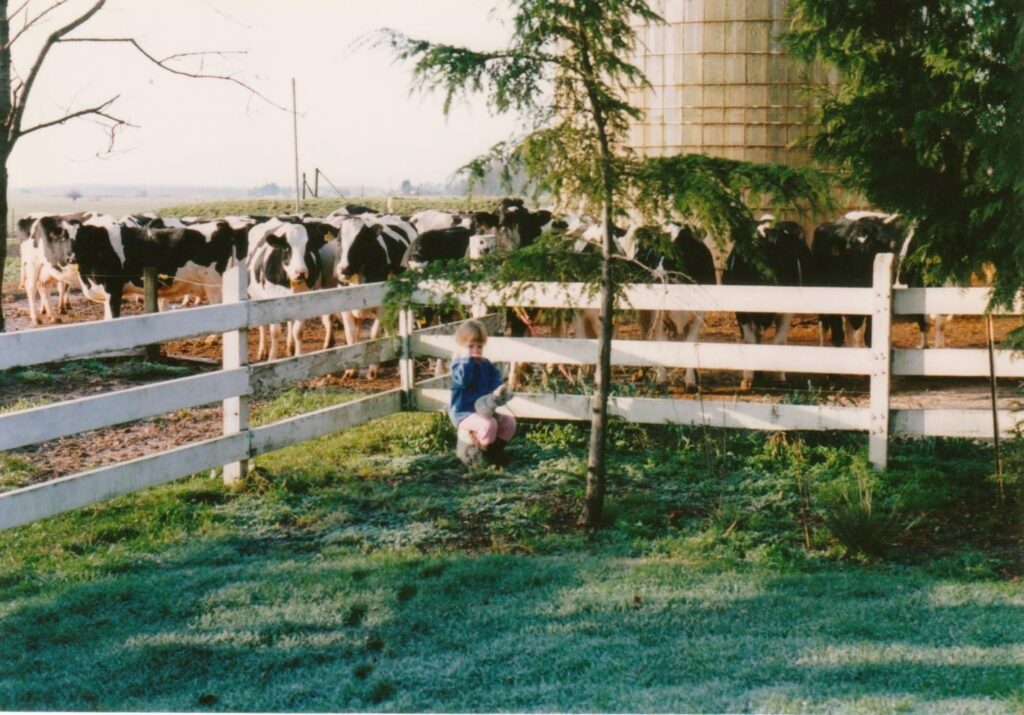

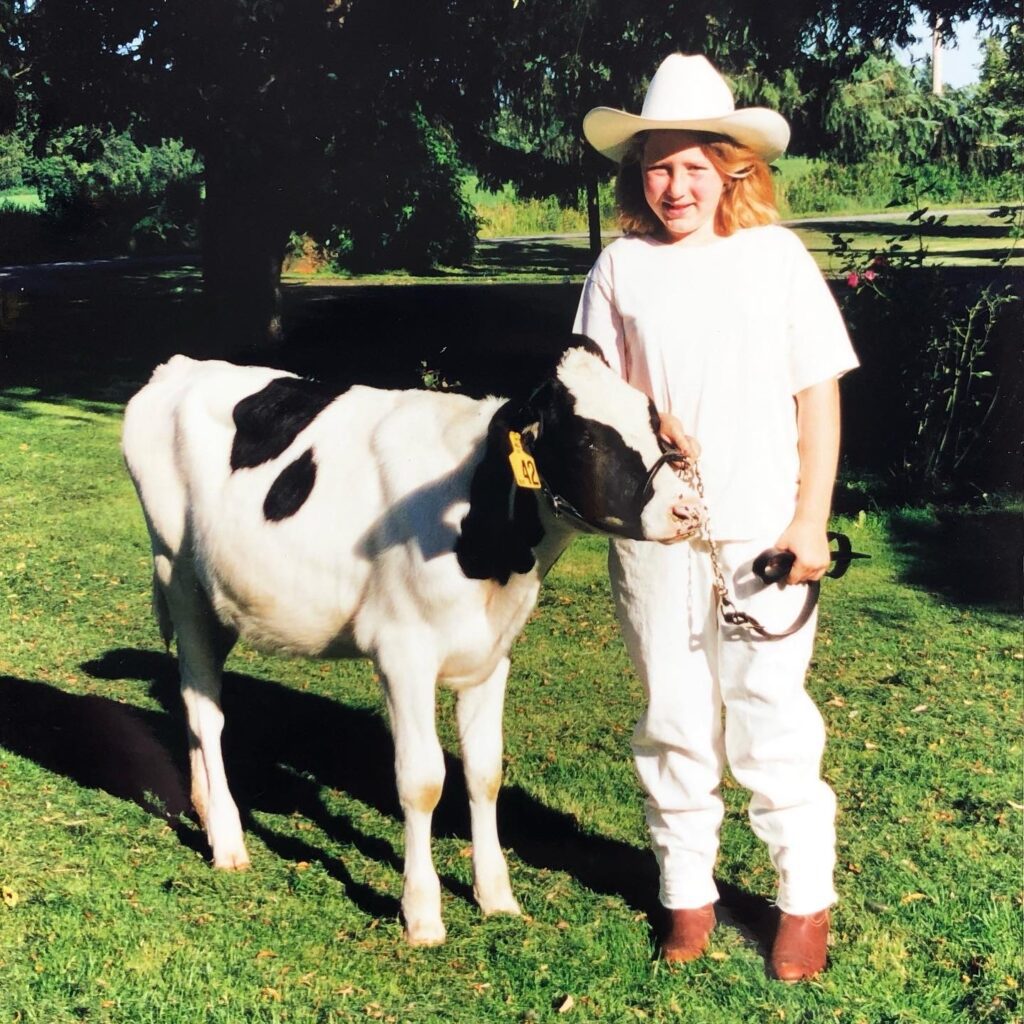

Kate, an ecologist and fourth-generation dairy farmer, is playing a role in maintaining her family’s longstanding Lynden business — but she’s also advancing it. A few years ago, Kate began exploring yogurt production as a way to diversify the operation.

It’s part of a larger trend: As U.S. agriculture aggregated, many Whatcom County farms began selling their milk to larger companies and cooperatives. This included the Steensma family, who ship milk to Darigold. When he was a child, Kate’s father, John Steensma, remembers about 1,000 dairy farms operating in the county. Now, there are 55. Many of them have upped their herds, too, and the Steensma farm of 200 cows is now considered smaller than average in the county, John said.

“As a dairy farmer, it’s getting harder to survive if we’re just selling it all to the bulk market,” Kate said. “There have been years in the past when I was growing up, where my dad would joke, ‘I pay for the privilege to be a dairy farmer’ because he loses money.”

As a farm diversifies its products, it offers more stability and opportunity for profit. Plus, consumers are gravitating toward locally made products in response to a food industry full of unknowns. Steensma pointed to a podcast she listened to that featured Bellingham chef Ona Lee.

“She’s said, ‘There’s something spiritual about being able to eat food that’s grown right where you live.’ And I think that’s really important,” Kate said.

In October 2021, Kate made her first sale. Since then, Steensma Creamery skyr, the first locally produced yogurt of its kind in the state, has made it as far south as the Ballard Farmers Market and onto the shelves of Puget Community Co-op markets.

“The best part is at the farmers market when someone’s walking by and they’re a maybe, so you’re like, ‘Do you want to sample,’ and [they’ll say] ‘OK, yeah, I’ll try it.’ And then they take a bite, and you watch their face go like, ‘Whoa, that’s really good.’”

Skyr, technically a yogurt-like cheese, is made with different bacteria than rival Greek yogurt, lending to a less-punchy flavor. Steensma Creamery skyr is also strained through cheesecloth to remove about 50% of its whey byproduct to make it extra-thick and creamy; Kate still uses her grandfather’s strainer that he brought with him when he moved to Washington state in 1969, plus ones she modeled after it.

Kate tweaked her yogurt recipe (which she learned how to make from John at the age of 9) to become skyr. She experimented with adding in fresh flavors to make maple, mango and raspberry skyr in addition to plain.

At Custer creamery Grace Harbor Farms, Kate processes about 40 gallons of skyr a week — using only a fraction of the family farm’s milk. She found support and space to start her business in Grace Harbor owner David Lukens, though they are effectively competitors.

“There’s room for everybody in the market if we’re all specializing in different things,” Kate said. “Nobody else here makes skyr. I’m not stepping on anyone’s toes.”

Expanding the business to yogurt had been John’s dream 25 years ago, he said.

“Except, at the time, my kids didn’t need a job, my kids were a job,” John said.

“He’s stoked,” Kate added of her dad, “but it also means his retirement is a little delayed because I can’t manage the cows all the time right now. He’s 65, so he’s very tired, but he’s also kind of invigorated by this.”

Kate’s return to the family farm was welcomed, but not pressured, she said. She graduated from Seattle Pacific University with a bachelor’s degree in ecology. No agricultural programs existed at the urban college, but Kate missed growing her own food. She and a friend started a gardening club and a community garden on campus.

“She and I both are farmers now,” Kate laughed.

She went on to grad school at Michigan State University, where she became one of only several people in the U.S. to earn a master’s degree in dairy cattle grazing behavior with robotic milkers. Her speciality led her to work for a company that makes robotic milking machines. Kate worked for them for around seven years, traveling the continent, and sometimes overseas, helping farms of all sizes implement technology.

During a work trip to Europe, Kate flew Icelandair, where she was first served skyr 35,000 feet in the air. She stayed in Iceland for a week on an “extended layover” and fell in love with the food. She also tracked market research, which showed Nordic and Icelandic food products were becoming increasingly popular, especially in the Seattle area.

Kate returned to her family farm in 2019 — after seeing the massive scale of some farms through her job, she missed the smaller herds she grew up around.

“If I was a cow, I would want to be on my own farm,” Kate said.

The Steensmas treatment of their animals is part of the reason employee Carrie Crockett was attracted to the job.

“It’s really important to me to work somewhere that lines up with my values,” said Crockett, during a tour of the creamery. “Animal care is really important to me. And this product is so pure. I sell it at the Ballard Farmers Market, and it just sells itself.”

As for the future of Steensma Creamery, Kate is happy taking their ascent into value-added products slowly and carefully. They do plan to expand production eventually, and that might include other foods like fresh cheeses. Perhaps they will even build their own creamery one day, Kate said.

“There are a few different opportunities that are starting to percolate, but nothing is set in stone,” Kate said.

“Big picture, things are working out,” she added.

Visit Steensma Creamery during Whatcom This Whey from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Saturday, June 10 at dairy farms throughout Whatcom County. Steensma Creamery fare will also be featured at an Edible Everson Farm to Table Dinner Series Saturday, June 17 at Alluvial Farms. Info: wadairy.org or alluvialfarms.com.