TULALIP, Snohomish County — In some families, the stories were passed down. Siblings separated, children locked in closets, their mouths washed out with soap, a second grader who froze his toes off trying to escape.

In others, the memories were just too painful.

“They really kept it quiet,” Karen Sheldon said of her parents, wiping away tears. “A lot of the little things that happened make sense now.”

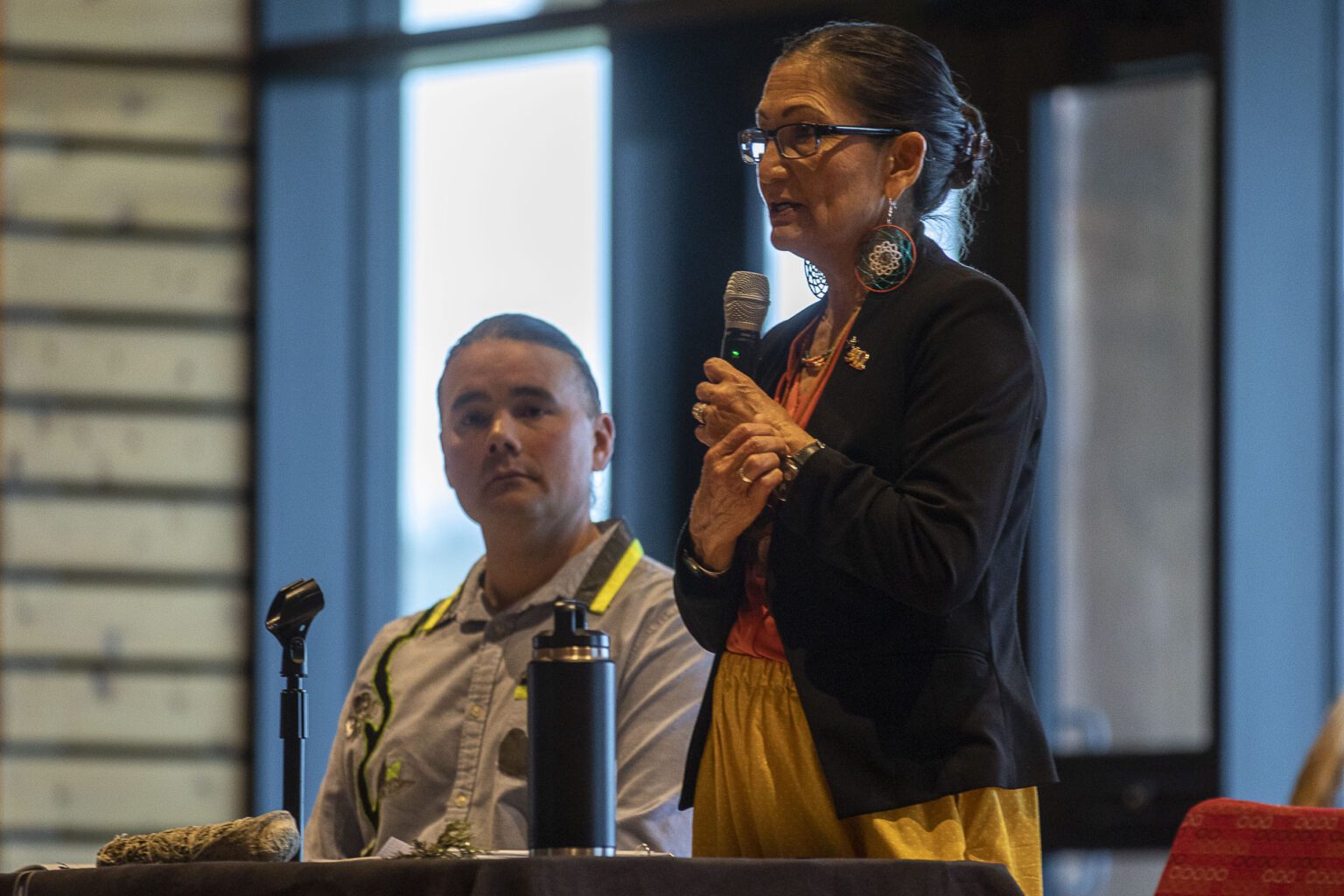

Their voices thick with emotion, survivors of Native American boarding schools and their family members took turns speaking to the crowd in the Tulalip Gathering Hall on April 23. The event was a stop on Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland’s “The Road to Healing” tour around the country, meant to give survivors a chance to talk about their experiences and access to mental health resources.

A year ago, the Department of the Interior released its first report revealing the scale of the boarding school system, in which Indigenous children were separated from their families in an effort to stamp out their culture. Among the report’s findings: at least 500 children died at 19 boarding schools, a number expected to increase with more investigation.

The boarding school era lasted more than a century, from 1819 to 1969. Generations of native kids attended schools across the country, at least 408 schools in total including 15 in Washington. In June of last year, The Daily Herald published “Tulalip’s Stolen Children,” a three-part series about the history and lingering trauma from the Tulalip Indian School.

Students endured abuse and illness. Some schools were so overcrowded they piled multiple children into a single bed. Escape attempts were not uncommon.

“Federal Indian boarding school policies have touched every Indigenous person I know,” Haaland said Sunday. “My ancestors and many of yours endured the horrors of Indian boarding school assimilation policies carried out by the same department that I now lead.”

Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland said “our federal records alone can’t tell the whole story.”

“We need more,” he said.

‘Never been about religion’

Matthew War Bonnet brought a “Jesus rope,” a rope with strands at the end, to Sunday’s gathering. Priests at St. Francis Indian School, which War Bonnet attended, beat children with ropes like it, as well as belts, sticks and razor straps.

“When you’re 6 years old” and you see other children get hit, War Bonnet said, “you get scared. You start holding things in.”

For eight years during his childhood, War Bonnet spent 10 months of the year away from his parents. The trauma of the experience stayed with him. In eighth grade, he tried to take his own life by hanging.

His voice breaking, War Bonnet said, “I don’t want my kids to feel that way.”

War Bonnet’s school was run by Jesuits, but he said he wanted people to understand “this has never been about religion. It’s been about people abusing children.”

The schools started a cycle of abuse, he recounted, with kids he went to school with becoming “abusers of themselves, abusers of their families, abusers of their communities, until they just quit.”

“I want the church to take responsibility for what it did,” he said. “Not only to me, but to our communities.”

‘We should talk about it’

Native American boarding schools left mental and physical scars on their pupils through abuse, but also through neglect.

Jewell James, a Lummi Nation master carver, remembered falling severely ill at school. His throat closed up to the point where he had to shove pills in with pencils. It wasn’t until a family member intervened that the school let James go to the hospital.

Another speaker said her mother told stories about the lack of food at school. The Interior’s report acknowledged children at the boarding schools were malnourished and were often fed unhealthy food.

The listening session was emotional for speakers and audience members both. Several speakers expressed gratitude for the opportunity to share their stories.

“We keep our secrets all the time,” survivor Ernestine Lane said. “We should talk about it.”

Before, Lane said, “I thought I might have been the only survivor of a boarding school. But it’s so good to hear and know that we’re all the same.”