Climbing is an important part of the outdoor recreation economy.

The $12 billion climbing industry brings tourism, recreational dollars and jobs to communities throughout the United States, but a key part of the climbing experience has long been contentious: The use of bolts on climbing routes.

There are two common types of equipment used to attach the rope and the climber to the wall. First, there is traditional equipment — or “trad gear” — that includes wedges and camming devices that can be placed in cracks.

Then there are bolts, installed in the wall for a climber to clip their rope into. Unlike trad gear, these bolts are semi-permanent. Land managers often refer to bolts as fixed anchors.

While many see bolts as permanent installations, they are not. Most have a 20-year lifespan before they are replaced. A bolt can also be permanently removed, and the bolt hole can be patched.

Climbers use bolts in a few different ways. Some climbing areas are constructed with lines of bolts up otherwise blank walls, creating routes. The routes in these areas are referred to as “sport climbs.”

Some long climbs are mixed, with bolts between crack systems to connect them.

Lastly, bolts are often placed as rappel anchors, allowing for descent. In all three cases, bolts help to facilitate a type of trail system up the side of a wall, increasing the safety and security of the climbers.

Two bolts at the top of a climb with a rope running through “Mussy Hooks.” (Photo by Jason D. Martin)

Two bolts at the top of a climb with a rope running through “Mussy Hooks.” (Photo by Jason D. Martin)

Since the drilling of bolts alters the rock, they have long been a point of contention with land management agencies and in the climbing community.

In some cases, the concern is about the rock itself. In others, it’s about the social trails created to access a climb or related to resource protection issues like endangered species or Indigenous artwork on the rocks.

Most climbers see themselves as land stewards, and every climbing area has its own bolting ethics given the nature of the rock and the surrounding environment.

There are strong internal area-specific policing mechanisms in the climbing community around the placement of bolts, but these mechanisms (often naming and shaming when bolts are placed thoughtlessly) are generally not enough.

In theory, land managers are supposed to create climbing management plans to address resource protection issues. These plans describe where, when and how climbing is allowed on public lands.

In practice, many land managers are underfunded and don’t have the resources to put toward comprehensive and well-thought-out plans that address all the potential issues, which sometimes leads to bolting moratoriums.

The 1964 Wilderness Act makes it even more complicated. The Act prohibits the use of machinery and installations in federally designated wilderness. Many land managers have interpreted this to mean that climbers may not use power drills in the wilderness, but may still use hand drills. Others see bolts as permanent installations and thus are not allowed.

Climbers believed much of this was cleared up in 2013 when the National Park Service issued Director’s Order #41 (DO#41). The order recognized climbing as a legitimate use of wilderness and authorized the use of fixed anchors — but noted they must be closely managed by park administrators.

Some park managers have critically read DO#41 in recent years and found loopholes. Indeed, despite the order, the language used in recent management plans has referred to bolts as “prohibited installations,” in places like California’s Joshua Tree National Park and Colorado’s Black Canyon of the Gunnison.

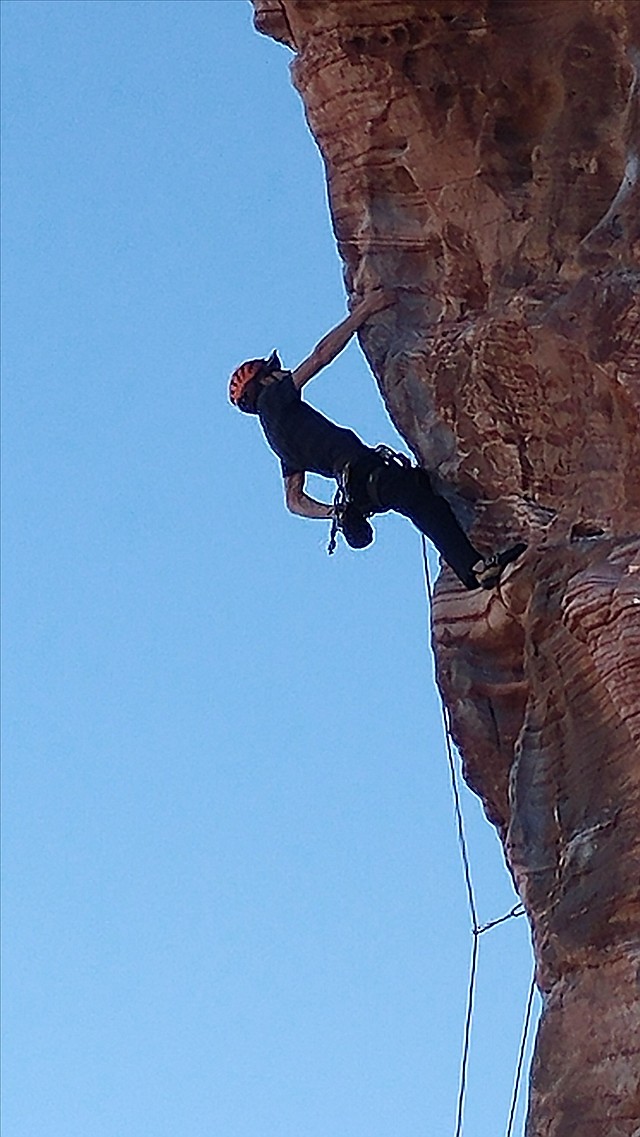

A climber on a bolted route in Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area. (Photo courtesy of Caden Martin)

A climber on a bolted route in Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area. (Photo courtesy of Caden Martin)

Early last month, the Protect America’s Rock Climbing Act was introduced into Congress by Representatives John Curtis (R-Utah) and Joe Neguse (D-Colorado).

The bill would allow for consistent management between all federal agencies for climbing in the wilderness. It specifically addresses fixed anchor management and the development of climbing management plans.

Though this bipartisan bill was introduced to Congress, there are some in the Republican-controlled House — and perhaps some Republicans in the Democratically-controlled Senate — who don’t want the current administration to have any legislative wins.

Some outdoor advocates believe this and another large bipartisan outdoor recreation bill (America’s Outdoor Recreation Act) may be able to thread the needle and have a chance to pass in 2023.

If not passed this year, these bills are unlikely to pass in 2024, as partisanship in a divided Congress will intensify in a presidential election year.

Fixed anchors are an integral part of the sport of climbing. The Protect America’s Rock Climbing Act will codify the historic use of these types of anchors while ensuring both the safety of climbers and the recreational dollars in the “climbing economy.”