Editor’s note: This is part one of a two-part series exploring the role of the Chuckanut Community Forest Park District and its relationship to the city of Bellingham and the surrounding community. Today’s story is an overview of the formation, finances and actions of the park district in its 10-year existence.

When the city of Bellingham asked the voter-formed Chuckanut Community Forest Park District to disband in September this year, it launched a 365-day countdown timer. The district has about nine months to stop taxing local residents, transfer the land easement on the Hundred Acre Wood to a different conservation entity and then to formally disband.

Elected commissioners for the park district — initially formed to raise funds to pay the city for part of the Hundred Acre Wood park to protect it from development — aren’t ready to do that just yet. In fact, park commissioners are raising the specter of what would amount to taxpayer-financed legal action against the city in an ongoing squabble between the two entities about the park’s future.

Instead, the decade-old park district, which fulfilled its mission of paying off a $3.2 million loan from the city earlier this year, voted to renew the district tax levy for 2023, projecting another $80,000 in tax revenue across the district next year.

Now, many residents who live within the special tax district are frustrated, and city of Bellingham staffers are confused, suggesting the park district has stepped outside of its role: If the loan was repaid, why is the park district still bringing in funds?

Formation of a special tax district

The 82-acre stretch of forest between Fairhaven Park and the Interurban Trail in south Bellingham wasn’t supposed to be a park. When the city of Bellingham purchased it in August 2011, employees eyed it for its original planned use — development, with structures and multifamily-zoned housing for a growing community.

Instead, payment for the land came from the city’s unique Greenways Program, with some of the funds promised from taxpayers. South Bellingham residents voted to form the park district, a new government entity capable of raising taxes and levies to pay off part of the purchase.

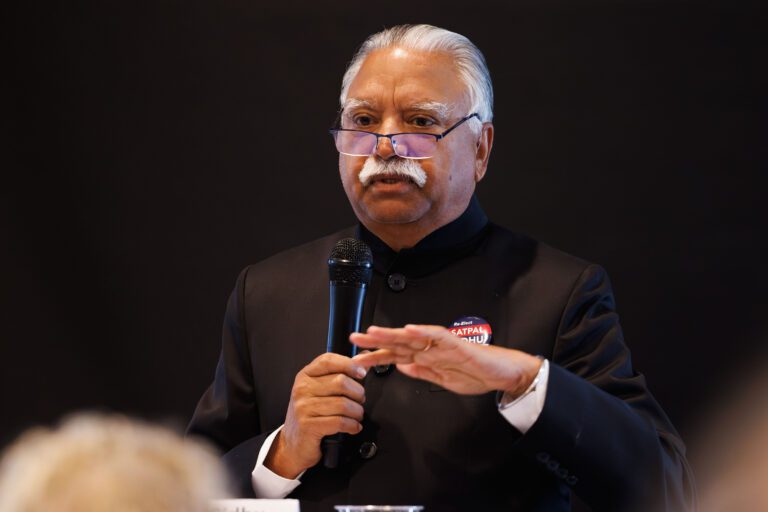

“What the community immediately adjacent [to the forest] did was tax themselves in order to preserve the property,” park district president Frank James said. “The city put up about $5 million, a little over half the value of the property. As the park district, we taxed ourselves as a community to provide $3.2 [million] in addition to that.”

James sits on the five-person board of commissioners elected to represent the South, Fairhaven and Edgemoor neighborhoods, as well as parts of Happy Valley and South Hill. When the park district was formed in 2013 after a vote, it established a property tax of 28 cents per $1,000 assessed property value.

“The city was looking at possibly carving off a piece of it and having it developed,” said Alan Marriner, the city’s attorney. “Once the park district was formed in 2013, we began negotiations.”

Both the city and the park district agreed to the set terms: pay off the loan (with interest) within a decade. In exchange, the park district got a conservation easement, a legal agreement protecting the Hundred Acre Wood from development “in perpetuity.”

Over the years, the tax levied by the district has fallen: from 28 cents per $1,000 valuation in 2013 to 4.6 cents per $1,000 valuation in 2022. With these rates, the park district paid off the $3.2 million loan, with interest, before the decade was up. It had enough extra to fund a legal defense when it was sued by taxpayers, as well as stockpile more than $200,000 in reserves.

(In 2017, the park district was sued by residents who claimed the taxes were illegal because the revenue was passed on to the city to pay off a loan. The case made it to the State Supreme Court, which found the taxes to be legal.)

In late November, the park district approved the 2023 levy rate: just 2.25 cents per $1,000 valuation, which will bring in an estimated $80,000.

When formed, the park district committed to dissolving once three things happened: First, the group finished paying the loan; second, the city committed to a “master plan” for the park; and third, when the city gave notice for the district to dissolve.

All three milestones have been met. The group finished paying off the loan earlier this year, and in September, the city certified the Chuckanut Community Forest Master Plan, a plan designed to “set priorities and strategies to guide the future” of the well-loved park, according to the city. On Sept. 16, the city gave notice for the park district to dissolve.

“They have to dissolve within one year,” Marriner said. “The timer is running out.”

But park district commissioners say there are outstanding requirements the city has yet to satisfy before the group can dissolve itself.

‘A park, not a preserve’

The city of Bellingham and the park district seem to disagree on the mission of the latter entity. While the city sees the park district as part of the initial funding mechanism for the Hundred Acre Wood, the park district argues its role includes oversight of significant conservation and preservation efforts.

“For the Chuckanut Community Forest, it’s always been recognized that both [recreation and conservation] are important,” said park district commissioner John McLaughlin, who has sat on the board since 2015. “We want people to be able to visit it, to be able to experience it, to be able to value it, but we also want to steward or retain the characteristics that make it so special.”

“This is the most protected park in Bellingham right now.”

— Bellingham Parks Director Nicole Oliver

During the early negotiations, the park district and the city met to hammer out a conservation easement, permanently nixing development and creating specific protections for the forest.

Now, the park district is working to renegotiate the easement, asking for further amendments and restrictions on uses in the park, including limiting trail access, rules about bikes and animals and stricter enforcement of existing laws.

Though city staff said they agreed to many of the requests, they couldn’t commit to all of them, particularly the request to add language “prioritizing ecological function above any other allowed use,” said Bellingham Parks Director Nicole Oliver.

“This is the most protected park in Bellingham right now,” she said. “Putting a statement like that would essentially make a lot of the park off-limits, and would not allow us to get the work done that we need to do.”

“This is a park, not a preserve,” she added.

Before the park district can dissolve, the group will have to transfer its easement to another conservation-focused group. They’ll only do that once the easement is “acceptable,” park district president James said.

“We are not at a point where we agree on those terms,” he said last week. “The Master Plan got us part way, but not all the way there.”

James said the easement will require significant protection from ongoing threats to wildlife, including off-leash animals and recreational bikers. Off-leash dogs are not allowed in the Chuckanut Community Forest or other city parks, but there’s limited enforcement of that law, James said.

“The city is not taking any enforcement action to make sure that that doesn’t happen,” he said. “That’s a main issue that needs to be resolved.”

Other park district concerns include which existing trails will remain open, which will be closed and which need to be “enhanced” with signage and boardwalks.

Negotiations over the easement will continue “over the next months, the next seven months, eight months, nine months, however long it takes so that we have a mutually agreeable set of principles that the park district and the city agree on,” James said.

There’s only one problem: If the conservation easement is not transferred before Sept. 16, 2023, it will disappear.

“They have [less than] a year to dissolve, and if they don’t, they lose the easement entirely,” Oliver said. “None of us want to see the easement go away.”

Oliver said the park district has stepped outside of its official capacity and role.

“The things that need to happen now are things that need to happen outside of the park district and their mandate,” she said. “It’s not that what they want isn’t legitimate. They want to improve the parks, and so does the Park Department.”

But, Oliver said, what the parks district wants requires enforcement, and the city doesn’t have a parks-enforcement division. The only enforcement arm in the city is the Bellingham Police Department.

A legal defense fund

The Bellingham Police Department is chronically understaffed and doesn’t have the manpower to respond to callers complaining about an unleashed pet on a hiking trail.

“The priority for the police department is violent crime or other serious threats to public safety,” park district commissioner McLaughlin said. “Trampling on trails and that sort of thing is a lower priority to the point where it really hasn’t been enforceable.”

The park district has gone so far as to consider funding enforcement teams and private security, as well as to sue the city for not following requirements established in the easement.

With almost $300,000 on hand this week, and more anticipated from the 2023 levy, they have the funds to follow through.

“The city was not willing to meet our needs in clarifying the easement and to ensure protection that we’re obligated,” McLaughlin said. “The idea was, if we can work in partnership then we wouldn’t have to extend the levy and we could end it, but the city was not willing.”

Now, the group plans to use those funds as part of a legal defense fund for the 82-acre zone. Much of the funding will transfer with the easement, as part of a support mechanism to ensure the easement is followed in perpetuity. Some of the funds, though, will remain in reserves over the next few months while the group fights for tougher regulations.

Eventually, commissioners of the park district said, it could lead to a lawsuit.

“Enforcement is beyond our authority,” McLaughlin said. “We could not hire rangers or enforcement officers and have them patrol. But, we can compel the city to, legally. We could bring suits against them for violations of the easement.”

Both the city and the park district say they want to cooperate, and a lawsuit would significantly damage those efforts. At this point, the park district has not instructed their legal representation, Bob Carmichael, to pursue a lawsuit.

The cash reserve is puzzling to city staff, though.

“They have over $270,000 in cash in their bank right now, and no other expenses that are foreseeable that could possibly be more than that,” Oliver said. “I don’t know what they would be suing us for, and I certainly don’t know if the community wants their property taxes to be paid to sue the city.”

The community likely does not.

“Conservation is important, and we understand that,” said Irena Lambrou, who lives across from the Hundred Acre Wood. “But the bigger question is, why are they trying to throw money away for this fund? There’s so much opacity with what’s going on.”

Moving forward

The park district knows renewing the levy in 2023 is a tough ask for the community, even if the rate is just one-tenth of the original levy a decade ago.

“We’re reluctant to extend the levy because it is precedent-setting,” McLaughlin said. “We don’t want to spoil the well for others who might want to use this strategy.”

Throughout the next nine months, the park district will collect taxes and review conservation organizations, seeking the perfect fit for an easement 10 years in the making. The group is considering several options, though the likely frontrunner, the Whatcom Land Trust, already possesses easements on neighboring properties.

The group will meet again on Dec. 14 and has already scheduled board meetings through Sept. 13, 2023, potentially the last meeting of the group.

Park district commissioners see the fight for the forest on a much larger scale.

“We’re coming up against a really hard-line environmental issue,” James said. “If we don’t change, there isn’t going to be a future for anybody.”

Tomorrow’s story explores the community’s response to the continuation of the Chuckanut Community Forest Park District.